The Rescued Recollections Concerning Ignacy Paderewski

Category

The Second Polish Republic

Donated by

Marcin Kapusta

Signature

IPN Kr 882

Maria Chełkowska’s mother, Zofia Donimirska, neé Mittelstaedt

Ignacy Jan Paderewski in the Eyes of Maria Chełkowska

Maria Chełkowska was born on September 13, 1878 in Telkwice (Sztum poviat), a daughter to Jan Donimirski, the heir of Buchwałd (currently Bukowo), and Zofia Donimirska, neé Mittelstaedt. She did not attend school, but received an excellent home education with an emphasis on Polish culture and patriotic traditions. In 1898, she married Józef Chełkowski, a landowner and socio-political activist.

The young couple lived in a mansion in Śmiełowo (Jarocin poviat). In opposition to the Germanization policy of the authorities in the Prussian partition of Poland, they made Śmiełowo a local center for spreading Polish culture, as well as the center of the ‘cult’ of poet Adam Mickiewicz. Over the following years, they hosted some of the finest representatives of Polish culture, art, and politics in their home, among others, writer Henryk Sienkiewicz, painter Wojciech Kossak, philosopher Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Gen. Józef Haller, and pianist and politician Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The Chełkowskis were also known for their philanthropic and organicist activity [a philosophy that states that the universe and its various parts (including human societies) ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism].

In December 1918, Maria Chełkowska accompanied Ignacy Jan Paderewski on his trip from Gdansk to Poznan. When the Wielkopolska Uprising of 1918–1919 broke out, she was one of the guests at the Bazar hotel that was fired on by Germans. In the following years she lobbied various politicians for the organization of armed uprisings in Pomerania, Warmia, and Powiśle, and even corresponded with military leader and statesman, Józef Piłsudski on the subject.

In October 1939, the mansion in Śmiełowo was taken by the Germans, and the Chełkowski family was imprisoned in an internment camp. After the end of WWII, Maria Chełkowska returned to Telkwice, but the hardships of daily life that she endured there forced her to move to Krakow in 1952. Maria and her husband had fourteen children. She died on March 18, 1960 at the age of 82. She was buried in Salwatorski Cemetery in Krakow.

Documents found in the package indicate that Maria Chełkowska started to write her memoirs in the late 1950s, thus fulfilling the wish of the wife of her youngest son, Andrew (b. 1922). Anna Żeleńska-Chełkowska had a PhD in history and was the author of a monograph about Feliks Radwański, a senator of the Republic of Krakow. There are many indications that at least some of the materials saved from destruction were once part of her collection.

Among them we find, first of all, numerous typed manuscripts of historical studies being prepared for publication, which were based on Maria Chełkowska’s memoirs. In addition, (indispensable in the work of any historian) there were index cards and correspondence regarding publishing plans. However the most interesting materials were found at the very bottom of the package: three photographs taken around 1870–1900 that show a young Maria Chełkowska (still Donimirska at the time) together with members of her family, as well as her handwritten memoirs concerning her later acquaintance with Ignacy Jan Paderewski.

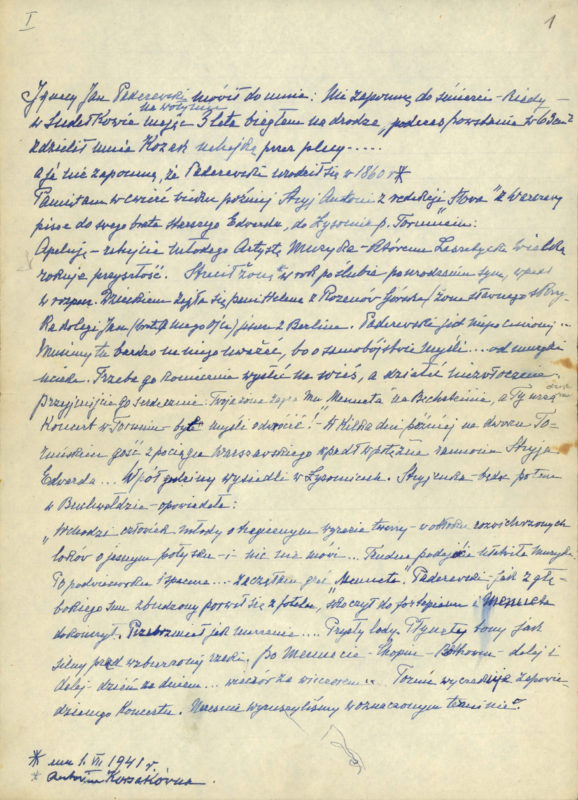

“Ignacy Jan Paderewski said to me, ‘I won’t forget until the day I die, I was three years old then, when I was running down a road during the uprising in [18]63 in Sułdyków, Volhynia, and a Cossack planted a whip on my back....’.” “And I will not forget that Paderewski was born in 1860.” These words begin an eighteen-page memoir in the cramped handwriting of Maria Chełkowska, devoted to one of the Fathers of [Polish] Independence.

Maria Chełkowska’s handwritten manuscript of recollections about her acquaintanceship with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, p. 1

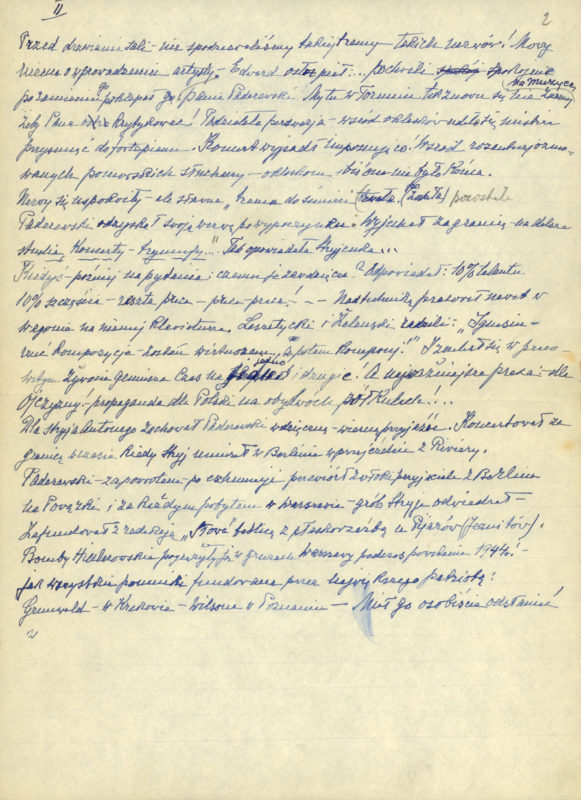

Maria Chełkowska’s handwritten manuscript of recollections about her acquaintanceship with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, p. 2

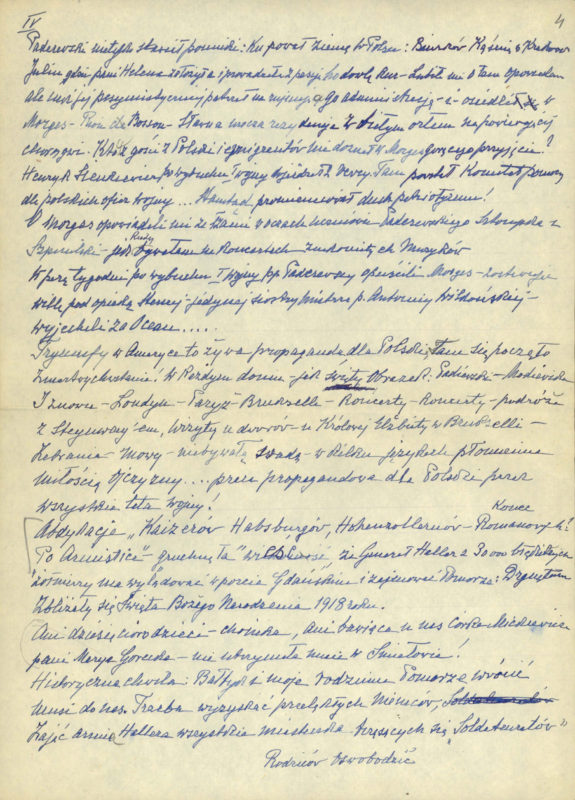

Maria Chełkowska’s handwritten manuscript of recollections about her acquaintanceship with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, p. 3

Maria Chełkowska’s handwritten manuscript of recollections about her acquaintanceship with Ignacy Jan Paderewski, p. 4

Acquaintanceship in the Shadow of the Great War

Chełkowska devoted the first part of her memoirs to citing known accounts from relatives connected to her family’s first contacts with Paderewski, when she was still a young child. The circumstances of his arrival in Łysomice, where her uncle Edward lived, were quite dramatic. In October 1880, shortly after delivering a baby, Antonina (neé Korsak), the wife of young pianist Paderewski, died. Chełkowska’s uncle personally took care of the despairing Paderewski, and helped him restore in him the desire for artistic work. After Paderewski’s respite in the country he even organized his first concert in nearby Torun. However, stage-fright took hold of the overwhelmed Paderewski: “Edward was petrified .... after a while, he calmly patted Paderewski’s arm and said, “Mr. Paderewski, here in Torun we do not know music well enough to criticize you.” As Chełkowska wrote further in her memoir, these words worked their magic and the concert was superb.

The first time Chełkowska had the chance to meet Paderewski in person was during his concert in Poznan in 1901. He was then married to Helena Maria Paderewska. In her memoir Chełkowska wrote that she had always admired the Paderewskis as an exemplary and inseparable couple. As can be seen from further reading, the two women were on very good terms. Paderewska especially liked to tell Chełkowska about the chicken breeding enterprise she had started on an estate bought by her husband near Krakow.

A real turning point in Chełkowska’s life was the approaching end of the Great War and rumors about the landing of troops commanded by Gen. Józef Haller [head of the Polish Army in France] in Gdansk: “Neither my ten children, nor a Christmas tree, not even Maria Górecka, Adam Mickiewicz’s daughter, staying at our house, were able to keep me in Śmiełowo! What a historic moment: the Baltic Sea and my native Pomerania must return to Poland. We have to take advantage of the frightened Germans and let Haller’s soldiers recapture all the towns and ‘Soldenrats’ trembling in terror, and liberate the parents!” Chełkowska left for Gdansk with her third son, Szczęsny (b. 1901), who delivered supplies for Haller’s soldiers. To her great disappointment they did not appear in Gdansk at that time.

Shortly before her return home she received news that Paderewski was approaching Gdansk, together with a British delegation: “Stop – we will stay. The whole day goes by on the frenzied preparations in the ‘Danziger Hof’ – a suite, flowers, rooms for the arrivals (...)”. In her eyes, welcoming guests on Christmas Day was magnificent. “To the British delegates, Paderewski praised the Polish kiełbasa (sausage), right from Buchwałd and splendid, such as he had not eaten since childhood. He rejoiced at the photographs of my brood arranged in a miniature tableau and placed at my table seat.”

The next day she left with Paderewski on a train for Poznan. The capital of the Wielkopolska region welcomed the great artist with ovations. That same day he gave a speech to a cheering crowd from a window of the Bazar hotel: “Mrs. Helena, with her usual concern, cried to him, ‘you will lose your voice.’ We drew him away from the draft to a splendidly furnished apartment with a view of Plac Wolności (Freedom Square), still called Wilhelmsplatz, opposite the former German ‘Eldorado’ theatre. Chełkowska especially remembered her conversation with Wojciech Trąmpczyński, later the Marshal [speaker] of the Sejm [lower house of Polish parliament], who, during a banquet in honor of Paderewski questioned the sense of Poland’s occupation of Pomerania: “I hotfooted it out of there.” “What? Who won the war, the Entente or Germany?”

The conversation was interrupted by shooting: “German bullets came from the Eldorado on the square [Plac Wolności], went through the windows of the Paderewskis’ apartment at the Bazar, and came to a standstill in the knees of [painter] Jacek Malczewski’s formidable woman (...). Detonations! Panic! The Paderewskis could no longer return to their apartment. They took shelter in my room, then deeper to the windows on the courtyard, where it was safer.” The Wielkopolska Uprising broke out. Franciszek, the oldest of Chełkowska’s sons (b. 1899), took part in it, among others.

A couple of months later Chełkowska had a chance to listen to Paderewski’s statement after his return from Versailles: “The speech was splendid. I listened awestricken, seated with Helena in a balcony in the Sejm chamber [lower house of the Polish Parliament]. During breakfast at the Paderewskis’ apartment at the Bristol hotel, the Maestro whispered to me: ‘I weaseled my way out somehow, it’s difficult to be confident in the middle of intrigue and the hindrances of Germans and other enemies.’”